Algiers is a

part of New Orleans that most visitors never see.

Its small Baptist churches, dangerous looking bars,

dilapidated houses and vacant industrial lots are

home to some of Americaās worst urban poverty and

crime, but good people also live honest lives there,

in a culture steeped in spirituality and religion.

Algiers is also home to Herbert

Singleton, one of Americaās acclaimed vernacular

artists, whose walking sticks, sculptures and

bas-relief panels form part of most major

collections of contemporary Southern folk art in

the US (and also appear in the Collection de lāArt

Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland). Sitting on his

front steps sipping a beer, Singleton eyes the

street running past his narrow front yard, and

muses on the 60-inch television set inside his

barely furnished home: he bought it after hitting

the lottery. Talent and will go further than luck

in Algiers, and in his front room, pieces of

driftwood and scavenged wood planks awaiting

revelations from his chisels and mallet are the

raw materials of Singletonās most reliable angle

on survival.

Singletonās

workspace is a patch of grass in his backyard and

the bare wood floor of his living room. With a set

of well-worn tools, he carves tree stumps and

limbs, cedar cabinet panels and cypress doors,

then paints their complexly layered wood surfaces

with a bold but limited palette of glossy enamel

house and car paint. He marks the walking sticks

and sculptures with geometric motifs, vivid color

contrasts, emphatic figures and depictions of

reptiles, and applies similar aesthetics to the

masterfully stylized bas-relief panels. All reveal

striking parallels with the traditional carvings

of West Africa, but their themes of racism,

violence and religion, and the handwritten script

recalling roadside signage and religious messages

from another era, are distinctly of the American

South.

Catch Me

If You Can

Herbert has been, from time to

time, preoccupied with this

Zarathustra-like hero who dances on the

abyss and spits into the mouth of the

volcano -- this panel is a splendid

realization of that theme. Cedar (41x21)

The subjects of Singletonās wood

panels also include depictions of street life in

Algiers: the black struggle, New Orleans jazz

funerals and biblical stories. Many read like

autobiography, written in raw, personal imagery,

both literal and metaphorical. Their simple,

cartoon-like figurations convey irony and humor as

well as stark emotions. One piece, showing a

shackled black man pursued by dogs declares: ĪMy

affliction have brought me to shame. I am among a

nation of people that have no mercy on the hearts

and souls of black people. I can only say this is

a good night to die.ā A sign on a casket in one of

his jazz funeral scenes reads ĪGlad You Dead You

Rascal You,ā a line borrowed from a 1929 song by

New Orleans jazzman Sam Theard and made famous by

Louis Armstrong.

Singleton has spent nearly 14 of

his 58 years in prison, most of them in the

Louisiana state penitentiary at Angola, a former

plantation once worked by African slaves. Two .38

bullet wounds testify to his violent past. His

furrowed face can change from a stoic mask to a

charming smile in a flash as he deflects questions

about talent or inspiration. ĪPeople make out that

my art is some kind of great thing, but for me it

aināt no big deal ö it pays the bills,ā he says.

Singleton started carving at age

17, first making voodoo-inspired walking sticks

from river driftwood. With a long tradition in

African-American culture, such sticks are perhaps

the most direct link in American folk art to

African influences. Gallery owner, art historian

and Singleton patron, Andy P. Antippas wrote in Souls

Grown Deep (1), that in both African and

African-American cultures walking sticks

historically played spiritual, functional and

decorative roles, and were used in witchcraft,

divination and healing ceremonies brought to the

New World by African slaves.

ĪIn Africa,ā wrote Antippas, ĪAs

migratory tribes became more settled, the walking

sticks once used as implements for herding or

warding off predators ·often became more formally

decorative staffs, usually bearing emblems of

hierarchal rank or social position among

African-American carvers, you begin to see

similarities with European canes·and the influence

of the Old Testament, with its many references to

staffs. Singleton makes both walking sticks ö

sometimes used in New Orleans for protection

against two legged urban snakes, and larger staffs

which convey power and authority with seemingly

priestly intent ö either in voodoo or referencing

Old Testament prophets. In his pieces, snakes

going up a staff represent the effort to re-enter

heaven and the snakes going down represent the

Fall into Perdition.ā

This

is a very personal piece for Herbert

with

a complex history (which will follow, upon

request).

Cedar, (41x23)

As with most African-American

vernacular artists, no readily apparent reason

exists for the strong African impulses in

Singletonās work. Speculation that there is an

inexplicable connection to African blood-roots has

fascinated many critics, but Herbert Singleton has

never revealed interest in African or other

ethnographic arts. Some of his carved doors are

remarkably similar to Yoruba panel doors in

present-day Nigeria, and his carved tree stumps

resemble Yoruba divination pieces to the deity Shango.

But the tall totemic poles also recall indigenous

cultures from the American Northwest. Antippas

concludes that these Īinterestingā parallels are

Īprobably the fortuitous results of the materials

he works with.ā

Voodoo is the indisputable link to

Africa. It was brought to New Orleans in the 19th

century by slaves from Haiti, and is still

intricately wound into the local culture.

Singletonās early totems, carved with grotesque

faces, included the words ĪVoodoo Protectionā. In

many African cultures, such pieces are used to

scare off wandering spirits. The hundreds of

spirits in the voodoo pantheon invest their power

in both African imagery and in corresponding

identities, including Catholic saints. Voodoo

symbols including skulls, crucifixes, coffins and

African animals, all inhabit Singletonās artwork,

alongside intrinsically personal representations

of decadent street life in Algiers, guns and drug

paraphernalia.

Many of Singletonās first walking

sticks were sold to pay drug debts to a local pimp

known as ĪBig Hat Willieā, who occasionally used

them as weapons. That relationship also led to the

first sentence in Angola, which deprived him of

nearly a decade of carving. On returning, the

artist went to work for a self-styled voodoo

doctor named Charles Gandolfo, assisting with

swamp tours, and taking visitors into the woods

for staged rituals. From the driftwood he picked

up, he returned to carving and Gandolfo sold

walking sticks for him, often adorned with

carvings of snakes and crocodiles, which became

known as Īkiller sticksā after a French Quarter

buggy driver supposedly used one to beat off a

mugger.

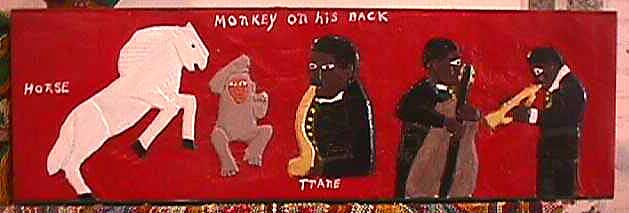

John

Coltrane: ''Monkey on

His Back.''

On the

far right, Singleton has intuited

the presence of Miles Davis. Part of

the Baltimore Visionary Museum's

exhibition.

Cedar,

(60x20)

Around 1988, Singleton started

experimenting with bas-relief panels. While the

raw materials of his walking sticks and sculptures

limited the compositions to natural wood forms,

doors and cabinet panels offered a broad, blank

canvas for his imagination. He initially drew on

voodoo imagery for inspiration, then experimented

with more personal subjects. Still recovering from

a near-fatal shooting and in the process of

kicking a drug habit, Singleton suffered from a

stomach ailment which he was convinced was caused

by snakes ö under a voodoo hex. Two

autobiographical pieces from that time interpreted

the illness through voodoo imagery and, he

believes, produced a cure. The first shows a

skeleton with red and yellow snakeheads poking

through its ribs: serpents representing his

unhealed wounds, his addiction, and the malignant

spirits which held him. A second piece shows a

black man pulling two large white snakes from

bodily orifices. ĪAfter I done it, that pain went

away,ā says Singleton. At the same time, he was

creating totems for a local spiritualist church

whose members ö like the voodoo practitioner ö

used them in healing rituals.

An outpouring of panels followed.

Their subjects ranged from the Old Testament to

the exploits of ĪMop Topā, a prison cohort who

terrorized fellow inmates with broken mop sticks.

Perhaps his most powerful pieces deal with the

struggles of Americaās black underclass. Singleton

strikes the difficult balance between

recapitulating stereotypes and ridiculing them in

broad burlesque. Drawing on history, New Orleans

street culture, and his own life, he interprets

not only the racial oppression of a dominant white

culture but also the self-destructive conflicts

within his own black community.

|

Strange Fruit:

Singleton's

response to the ''Without

Sanctuary'' exhibition reflecting

upon the

Southern ''tradition'' of

photographing lynchings. The

design of the

tree must be considered brilliant.

Carved, in this case, from a pine

panel. (59x19)

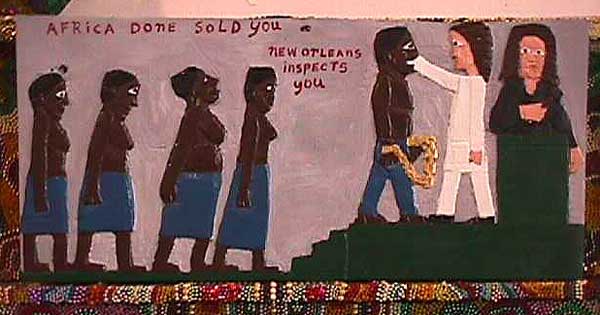

New Orleans

Slave Auction: ''Africa Done

Sold You

New

Orleans Inspects You.''

Cedar, (41x20)

|

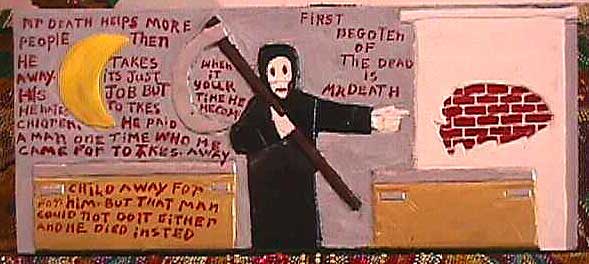

Mr.

Death:

An

unusually text filled piece

which

will be explained at length.

Cedar (44x20)

Killer

Stick

Singleton

has not made a ''killer

stick'' for a decade. This is

a vintage staff from c.1990.

It features a demon's head at

the top, a trident at the

bottom, and a snake creeping

up the shaft.

Oak, (59'')

|

|

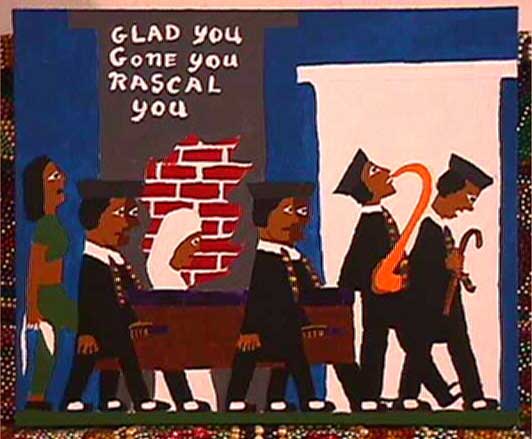

Glad

You Gone You Rascal You:

A

rare painting by Herbert.

Oil Enamel on Canvas

(20x24)

|

Among his

most visually complex and detailed pieces,

Singletonās biblical panels often draw on personal

experience whilst seeking broader truths.

Humanityās sinful nature, a search for salvation,

and the retributions of a personal God are

recurrent themes. A recent example, ĪHell is

Deep and Hot,ā shows archangel Michael

defeating Satan as two African angels fall into

the dark abyss. Accompanying text reads:

ĪWhosoever causeth a man to go astray in an evil

way shall fall himself into his own pit·You can

see the prophecies of Revelations out on that

street ö brother killing brother, daughter against

the parents and parents against the daughters. The

Bible says all of that was coming to pass.ā

Although he

knows the Bible from cover to cover, Singleton is

no churchgoer. ĪThe Bible is right there for

anyone who wants it ö thatās my church, all the

church I need. What voodoo comes down to, what it

all is, is faith by proxy...donāt matter if itās a

voodoo queen or preacher or psychiatrist. Itās

faith by proxy.ā Turning to a cedar panel,

Singleton returns to his carving, not knowing

where the piece will take him but sure that

paradoxes and revelations are waiting in the wood.

1. Souls

Grown Deep: African American Vernacular Art of

the South. Volume One, eds. William Arnett,

Paul Arnett. Tinwood Books, Atlanta, Georgia,

2000.

http://www.rawvision.com/back/singleton/singleton.html

Dr.

Kilikey, the Heroin Man:

A

dreadful fellow upon whom West Bank

junkies called when they couldn't

find a vein. Part of the Baltimore

Visionary

Museum's exhibition.

Cedar, (41x21)