2331 St. Claude Ave and Spain, New Orleans, LA 70113 • 504- 710-4506 • Tues-Sat 11am-5pm • Directions

|

2331 St. Claude Ave and Spain, New Orleans, LA 70113 • 504- 710-4506 • Tues-Sat 11am-5pm • Directions |

| Herbert Singleton ~ The Deity of Deception and Trikeration |

|

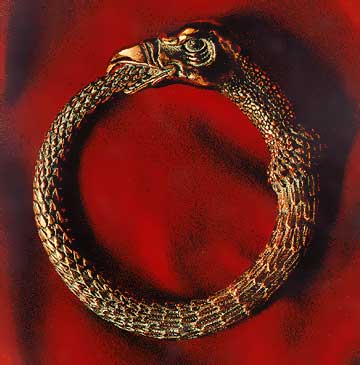

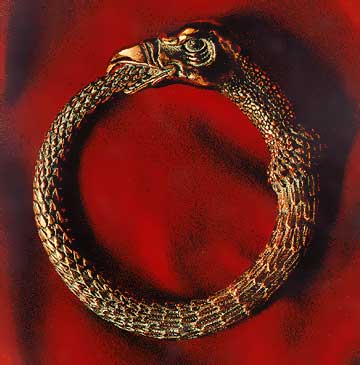

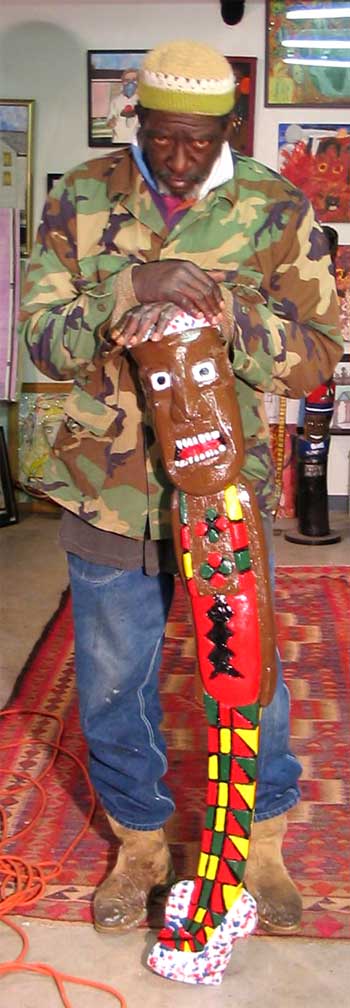

by Andy Antippas I'd like to share with Singleton's admirers a sculpture I consider, both in conception and execution, one of his greatest works—he painted the title on the back, near the base of the sculpture: The Deity of Deception and Trikeration Due to the stress of Hurricane Katrina, as probably everyone knows, Singleton's already fragile health was further compromised. While his entire family sought refuge in Houston, he chose to stay behind in his Algiers neighborhood, across the river from New Orleans. Algiers did not suffer from the same flooding which destroyed so much of New Orleans, but the winds were severe and a tree went through the roof of his family's home, where he was staying. After the storm had subsided, Herbert went out on his bicycle to find food and a chain saw; he collapsed against a fence. He later told me he became blind for a while, and I think he probably suffered a stroke--his right hand had seized up. According to some of his neighbors, the National Guardsman found him some time later, suffering from exposure and incoherent. For two weeks after the storm, Singleton’s mother and I tried to locate him by calling every military hospital installation in town. Luckily, Singleton was able to remember my gallery's number, and some four weeks after the storm, a doctor called to tell me Singleton had been cared for in Baton Rouge, and he was ready to come back to New Orleans. I went to visit regularly to help with his prescription costs and to chat. The stories he told me about his experiences during and after the storm were utterly nonsensical and clearly the result of hallucinations: waves of water pounding the sides of the house, his grandmother rescued by a helicopter from a tree, one brother shot and killed in the back yard, and another brother sodomized, shot by men in paper bag masks, and thrown off the roof. His doctor, although scrupulous about Singleton’s privacy, finally suggested he must have suffered liver damage during his collapse which released toxins to his brain resulting in the bizarre tales. I could never figure out what his medication was for, and I was never comfortable with the death notices saying Singleton died from cancer. It is more likely he died from systemic failure. I was anxious to get him back to work so he could put these outrageous stories down on wood; however, no matter how often over the months I came by to encourage him, and how many chisel sets, cedar boards, and other art supplies I brought to his home, nothing could shake him out of his torpor and depression. I decided to lug The Deity over to his house, along with some cans of Rustoleum, the figure’s dominant colors. We set it up by the door to his back yard. I suggested the piece could use a little freshening-up—which it didn’t, and he rightly looked puzzled, but he agreed to clarify some details at the back of the piece. Singleton had a special relationship with The Deity. He carved it in late 2004. He, more or less, suggested I not sell the piece. I had an iron base made for it and it stood in the back in his work area at my old gallery on O. C. Haley Blvd. After a while I noticed the slow accumulation of candy wrappers, worn out Craftsman chisels, broken mallets, and Pabst Blue Ribbon beer cans around the base. (Note: from 2000, when he began to take the ferry and bicycle over to work at my gallery, he would stop on the way to pick up a six-pack of PBR, which would be drunk by 4:00 when he left to return home. Mortified that anyone I knew would drink PBR, I suggested, "At the very least drink Bud." He responded, hilariously enough, "Heineken, Fuck that shit! Pabst Blue Ribbon!"—Dennis Hopper's immortal line from one of Singleton's favorite movies, "Blue Velvet"). Seeing the shrine-like accumulation of offerings to The Deity made me mindful of Singleton's sometime Voodoo beliefs--not dogmatic or systematic, but intuitive, absorbed from his environment, probably some auntie, his grandmother, or the older folks he grew up around in his youth. The Deity of Deception and Trikeration was more than a Lar familiaris; it was more than the Christian serpent of Paradise; I came to understand it was a representation of Papa Legba of Haiti, the Eshu of Dahomey, the Eleggua of the Yoruba pantheon--the door opener, the gate keeper, the emperor of the crossroads, the emissary between the phenomenal realm and the divine. Legba is the promoter of verbal facility, of double talk, the arch deceiver, not malicious, but a jokester, a prankster--the preeminent trickster god—like John the Conqueror, the guileful scourge of the Louisiana and Mississippi plantation owners—the trickster who will make a fool of you or scare the hell out of you, either just for laughs, or to teach you a lesson about life. Certainly Singleton called the sculpture by Legba’s name--but did he know Legba's colors were often red, green, and yellow? Or were they, coincidentally, the colors he happened to have handy that day? Did he know that Legba was represented in rituals as an erect penis, or did the oak branch he chose accidentally happen to be ithyphallic? Did Singleton give the piece a decided serpentine form because he knew Legba/Eshu notoriously caused snakes to bite folks on the way to the market and then sell them a cure? Singleton wouldn't have read about these things in books as I did, instead, he sensed them from a natural impulse imparted from growing up in New Orleans where the Haitian gods, brought to the city by the Yoruba household servants of the plantation owners fleeing Touissiant L'Overture's indomitable fighters, grow, unbidden, out of every moist crevice of our city. There was one occurrence, however, regularly repeated, which left no doubt in my mind that Singleton himself actually harbored the quintessential spark of Papa Legba. When Singleton would come out from the back of the gallery, heading for the refrigerator and a PBR, and I happened to be talking to some clients, I knew I was doomed. Singleton’s eyes would sparkle with devious good humor, he would do a theatrical shuffle up to us, and I always knew what was coming: "Masta Andy," he’d say with downcast eyes and a calculated obsequiousness in his voice: "I done finished cleaning the shit out of the stables. Can I get myself a beer and rest up a bit before I get to the cotton?" Each time he did some variation of this routine on me, I would inevitably end up standing mortified, with my clients looking at me as if I were an inhuman slave-owning monster. I would nervously tell them the rudiments of the complex truth. I would explain he was only kidding, that he did this to me on a regular basis, and it was only a running gag at my expense intended to embarrass me—which it certainly did. Almost all thought it was clever. When he first began to play out his prank, I felt a bit of anxiety: how much truth did Singleton think was in what he was suggesting? Did he feel what I took, (at the end, almost 20 years), to be a warm, personal friendship between us was only a spurious imitation of a friendship? Was I victimizing him, taking advantage of his genius? After about the sixth or seventh time, I finally talked to him about his theatre and told him how uneasy it made me. His explanation testified to his great sensitivity, his intelligence, and his highly developed trickster personality: "I’m going to do this all the time to remind both of us, you and me, how difficult our friendship is and how good it is that we continue to be good friends." Much of his tricksterism is even clearer to me in retrospect. For example, the unnerving video interview he did in 1999 with me for Markus Wittmann’s “Life and Death at Barrister’s Gallery,” I tried to get Singleton to talk about the social criticism of the African American community inherent in his work, but he persisted on distastefully talking about inmate buggery at Louisiana’s Angola Prison and its insidious effects, which no amount of video editing could disguise. After multiple viewings, however, I finally came to understand the grotesque account was, in fact, a complicated allegory about the self-destructiveness of the African American community: that events in prison were no different than events in the streets, both characterized by domination and cruelty. It even occurs to me now his very mode of creation was a reflection of Papa Legba's compulsion to create chaos/confusion in order to bring about a new harmony. Watching Singleton take a smooth, untroubled cedar panel and destroy it with his chisel and mallet, gouging pathways and crossroads through the wood, I realize he was opening the gate between the mundane plane of the cedar panel and the new, ultimately transcendental beauty of his work. Legba was more than Singleton’s personal god—Singleton was the embodiment of Legba—intelligence and cunning, misdirection and humor, art and artifice—the mean attributes allowing survival in prison, the violent streets of New Orleans, and essential, perhaps, to becoming a great artist. A couple of weeks or so after I brought The Deity to him, he called to tell me he was done, and to come and pick it up. The scales on the back of the figure gleamed with the fresh coats of enamel paint, but there was not much enthusiasm in Singleton’s face. “I can’t carve anymore,” he said, “my hand is all curled up, my stomach is filled with acid, my chest hurts, my throat is sore. Don’t ask me to, I can’t do it anymore.” He reached into a corner and pulled out a grimy stretched canvas with latex paint smears on it: “But I’m going to try and paint something on this for you, it will be easier for me. Maybe by next week. I have some old tubes of paint.” I was, needless to say, completely dishearten at this definitive, conclusive statement. “The world is waiting for a Singleton Katrina piece,” said Gordon Bailey, one of his most ardent supporters and collectors: but it would never happen. Singleton’s hallucinatory visions of his Katrina experiences would have communicated the complete lunacy and the suffering of those days every bit as well as Spike Lee’s documentary. I was anxious to see what Singleton would paint on the canvas and whether, hopefully, some Katrina subject might still emerge. Perhaps he could round out his career as a painter, without the physical stress of having to carve into wood. He had done very few flat surface paintings in the past; I recalled he painted on two wood panels around 1995 for a collector’s New Orleans steak restaurant and, at my request, he painted a juke joint scene on a stretched 4'x 4' vinyl sheet for a client in Los Angeles—which was unfortunately destroyed in transit by UPS. He was a conscientious painter, and it would often take him longer to paint the relief figures on his panels as it did to carve them. He called a few days later. It was early June, 2007, and Singleton would die on July 25th. I went out to his home, and he presented me with a portrait …of Pope John Paul ll. Dumfounded, I asked what this was all about. He just laughed and shrugged his shoulders. It was one last prank.  Herbert Singleton's portrait of Pope John Paul II |

"Voodoo Pole", click for enlargement |

"Voodoo Pole", detail, head |

"Voodoo Pole", detail, heads |